WEDNESDAY, 12 OCTOBER 2011

In recent years, despite generating an historic amount of research in fields barely imaginable a generation ago, science has hit an all-time low, due to low public opinion resulting in lack of political and financial support. Events such as climategate at the University of East Anglia as well as misunderstanding over developments such as genetic modification, cloning and stem cell research have led to the public becoming disillusioned with science and this has allowed policy makers to question the role scientists play in the modern world. This is at a time when the world should be relying heavily on scientists to solve global issues such as diminished fuel reserves and increasing human population.

The “Threats to the University, Humanities and Science” conference held in Cambridge in July, sought to bring together leading figures from a variety of fields involved in the modern university. Representatives from government and university governance came together alongside lawyers and scientists from around the world to discuss the range of challenges which will shape the next 10 years of academia.

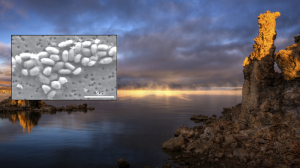

Miscommunication between scientists and policy makers was one of the major foci of the event. Science has long been seen as a key influence when designing governmental policy however the relationship is often tense. James Wilsdon of the Science Policy Centre at the Royal Society stated that it is vital not to point the finger at either party - both sides are often guilty of oversimplification and underestimating the other. He also highlighted that public support is generally key to the successful advancement of scientific fields. Matthew Freeman of the MRC Laboratory, Cambridge highlighted that the public’s view of science as consisting of hard immutable facts, is at odds with the reality, particularly when relating to advising policy. This is generally considered to be a failing of the manner in which science is taught at school, giving no hint of the uncertainty that is inherent in all scientific research. The view of science as consisting of uncertainty, scepticism and repeated experiment, while more representative of modern science, is often perceived by the public as a division in scientific opinion and thus it is devalued. This was highlighted by the very public scientific debate that took place in late 2010 over the finding that certain bacteria may be able to incorporate arsenic into their DNA structure.

Lawrence Krauss of Arizona State University had the view that scientists need to learn to sell their product to policy makers rather than simply assuming they will be interested in what they have to say. This is a key area in which the scientific community lacks an understanding of the policy process and its nuances. For scientists the facts are the whole story, while policy makers must balance this advice with other factors such as economic concerns or public opinion. An often quoted example of this is the policy surrounding genetically modified food; despite clear scientific evidence the public concerns were an overriding factor in determining the eventual policy decisions.

The failings are by no means limited to the academic side of the relationship; Martin Rees, Master of Trinity College Cambridge, raised the fact that scientists are poorly represented within politics which leads to a lack of understanding within government of the scientific method. There is a fundamental disparity between the long term research which forms the majority of academic work, and the short term concerns regarding health scares and natural disasters which form the majority of topics for which the government requires scientific input.

Professor Rees combined many of these themes in his 2010 Reith lectures when highlighting the need for science to communicate more effectively;

Often science (has) an urgent impact on our lives. Governments and businesses, as well as individuals, then need advice – advice that fairly presents the level of confidence, and the degree of uncertainty

Having identified that both policy makers and academics need a better understanding of the processes involved, the question was raised of how best to resolve this issue. Increasingly politicians and academics are spending their entire career in their particular field with only limited movement between the two careers, it is necessary therefore to educate the parties as part of their professional training. This concept can also be expanded to cover educators, teachers, lecturers, university officials and regulators of education but must start within the context of a university education. Traditionally there is little mixing between the sciences, humanities and the arts leading to graduates having a narrow range of knowledge preventing them from being well informed regarding other fields. Although a broad education often prevents students from acquiring sufficiently detailed understanding to make a strong contribution to any field.

However simply educating scientists and policy makers in their counterpart fields will not fix the problem, there is still a significant problem in getting the interested parties to communicate efficiently. Only by bringing key policy makers and scientists together in a suitable environment can a frank and honest dialogue take place.

These themes of clearer communication with the public and government agencies were present throughout many of the discussions, in particular with regards to data protection and freedom of information laws. The perceived closed nature of many academic institutions leads to a lack of trust which in turn creates an atmosphere of fear and doubt, which must naturally be reflected in the policy of a government wishing the be successful (in terms of public opinion). Only if the scientific communities make their work suitably transparent can they regain the trust of the public and thus justify political support.

The conference also discussed the role of libel and freedom of information laws within a university context. Science writer and libel campaigner Simon Singh was present to put forward the view that the current UK libel laws are stifling academic discussions by creating an atmosphere of trepidation around speaking out against inaccuracies for fear of being sued. This has lead to academic journals being reluctant to publish negative or controversial results for risk of litigation. Additionally the weak laws in the United Kingdom attract foreign nationals to use our courts to hear cases based mainly overseas to increase their likelihood of winning (Libel tourism). Generally it is felt that libel laws are not suitable for the modern digital age (many laws depend on information being in print not accessed as online media) and fail to provide the same level of protection to academics and bloggers to that which journalists and authors enjoy.

It is however, important to point out that the majority of libel cases are found in favour of the defendant, or the cases are thrown out, often never reaching trial. In this respect the current system is working well, with frivolous cases being identified and stopped. This view overlooks certain key points however; there is still a significant cost associated with these failed cases, which is often never recovered from the losing side. Additionally it is impossible to measure the extent to which the threat of libel prevents publication in the first place.

Freedom of information legislation is increasingly becoming an issue for universities. Due to the funding received from government bodies, universities are considered public bodies and therefore subject to freedom of information laws. There is however an ill-defined boundary between the governance of the university and the research activities, and what information should and should not be freely available to the public. While it is central to the scientific process to publish and share findings, releasing data prior to publication risks undermining the eventual findings while the release of raw data risks misinterpretation. A number of funding bodies are however tackling this problem head-on both the Wellcome Trust and government research councils are now requiring academics to make their data more readily available along with details of the analysis. Additionally, many funding bodies are investing heavily in scientific communication programmes and rewarding scientists for involvement in outreach and public engagement schemes.

At the close of the meeting it was clear that by bringing together specialists from a range of backgrounds, the conference was able to offer a unique insight in to the challenges facing universities around the world. Perhaps the most interesting result of the meeting was to highlight the common ground and indeed common solutions for many problems facing both the academic and policy worlds. Through continued meetings of this type it is likely that solutions to many of these problems will be determined and with sufficient resolve these challenges can be overcome.

Written by David Bosworth