WEDNESDAY, 3 OCTOBER 2012

The flaming lips nailed it. The scientists racing for ‘the good of all mankind’ on the opening track Race for the Prize in 1999’s album The Soft Bulletin capture that fear of being beaten to discovery (‘the cure that is the prize’). Not only does the track encapsulate the fevered obsession that accompanies specialisation (‘both of them side by side, so determined’), but Wayne Coyne also screeches that the academics in Race for the Prize aren’t superheroes. After all, “they’re just humans, with wives and children.”Type ‘scientist’ into Google image search and you’ll realise that The Flaming Lips had a rather uniquely well informed idea of what a scientist is. The stereotype of the bespectacled, chemical-wielding maniac still abounds. Brian Cox resembles a rockstar in comparison. Scientists, according to search engines, aren’t normal: they’re brains wrapped up in lab coats.

Those pristine gowns have, time and time again, been the most highly cited publicly perceived accessory of the scientist; in Argentina it even forms the national symbol of learning. Clinicians however, although identified most strongly with the white coat, only began wearing them towards the end of the 19th century in an effort to portray themselves as scientists and to distance themselves from the mysticism of quackery. Early photographic evidence traces late 19th century doctors moving from beige coats to white, and wearing a black form of the coat, reserved for dissecting cadavers, less and less. Whether the white coats were chosen specifically to unite medicine with science, to announce a change in hospitals from buildings in which one was admitted to die, to clinics of healing, or to act as a cloak of purity when engaging intimately with patients’ bodies, the coat stuck. Only in 2007 was the white coat phased out by the NHS in the UK. A fear of spreading infectious diseases was cited for the adoption of scrubs in place of white coats, despite that being among the reasons for their original adoption.

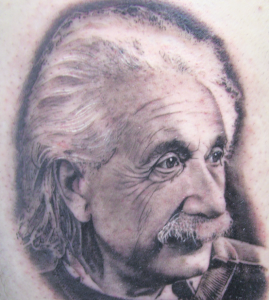

I don’t particularly mind my lab coat. Actually, I borrowed mine about three years ago from a rather petite girl in Bristol and never gave it back. But I don’t have to wear it all the time: I’m lucky in that I don’t work in a ‘wet lab’ which means I don’t have to dodge acids, alcohols or fluorocarbons. Neither did Einstein, and yet the modern crazy-haired mad scientist meme is sadly based largely on him. Indeed, while the coat is regarded publicly as the uniform of the scientist, throughout my time spent in academia I’ve learnt that this is a fallacy. In fact, the closest thing scientists have in terms of a uniform is a pair of headphones; no matter what specialisation you’ve chosen, all forms of science require at least a little mindless data entry, repetition and nail-biting, finger-crossing interludes whilst something does something to something else. Why not listen to Bjork whilst that happens?

The isolation of scientists away from society, within laboratories, may have helped contribute to the meme’s persistence. The ‘Draw a Scientist Task’ devised by David Chambers in the 1980s asked participants to sketch their interpretation of a scientist before and after meeting one. Almost universally the participants first drew a bearded, white, spectacled man in a lab coat. The same task was later adopted by the ‘Who’s A Scientist project,’ in which seventh graders were introduced to physicists at the Fermilab high-energy accelerator in the US. After this meeting, all of the children engaged in the project realized their mistakes and the subsequent drawings and descriptions illustrated ‘normal’ men and women who were, oddly, pretty interesting.

That was 10 years ago, but earlier this year the internet hummed with news of a similar project: science communicator Allie Wilkinson’s This Is What A Scientist Looks Like blog. As a collection of real-life scientists’ mug shots, the contrast to Google’s image search is stark. Yes, at least one of the images belongs on Awkward Family Portraits and yes, there are way too many ‘hilarious’ fancy dress costumes, but most are, to plagiarize Douglas Adams, “just these guys, you know?”

In his 1882 The Physician Himself and What He Should Add to the Strictly Scientific, D. W. Cathell recommended that the physician should “[avoid] forcing on everybody the conclusion that you are, after all, but an ordinary person.” Any uniform can be a wall to understanding and the proliferation of The Scientist meme proves that the public still view scientists as out of the ordinary, maintaining the 19th century mythology that medics constructed for themselves.

But those who seek to counter the public’s (largely erroneous) idea of what The Scientist is should be aware: the fight for the recognition of normality can backfire. The person who feels comfortable uploading a picture of themselves onto a publicly available tumblr blog also, one would imagine, likes to put themselves out there generally, as is more than evident in the amount of links to blogs and twitter accounts that accompany the photographs. And so the balance tips towards the extrovert. Carl Zimmer’s latest book is a perfect example of this. Science Ink gathers together images Zimmer had amassed on his blog after calling for scientists who had work-linked tattoos to forward photographs to him. I won’t pretend it’s not a fun book, and as I studied for my undergrad with one of the legs showcased, I can’t be too mean-spirited. But is an anatomically accurate tattoo of a chloroplast really that normal? Well maybe it isn’t. Let’s return to the Lips.

Race for the Prize’s heroes were obsessive. The song finishes with the lament ‘Theirs is to win. It will kill them’. No matter how ‘normal’ scientists are, there’s always a hint of addiction and the very act of science itself is time (if not all-) consuming, and dependent on repetition, thoroughness and compulsion. Without a willingness to sacrifice at least a little time others can spend in the pub, the scientist is doomed to fail. So perhaps I’m being too harsh. Is theirs an unnatural obsession, or just a necessary passion for their work? Underneath their coats, the geologists in Zimmer’s book have geological logs (which really are beautiful) painted on their backs, the biochemists have equations, and the conservationists have bees. Surely the sight of an Osprey on the leg of an ornithologist is a sign of sincerity in their work, a permanent mark that reminds us of how deep their commitment to their subject really goes? Maybe this is what we really want in our scientists?

So while ‘This Is What A Scientist Looks Like’ is an enjoyable romp through a hitherto hidden diversity, the #IAmScience hashtag that paraded around Twitter was much more informative. In describing how scientists began their careers it generated a collection of vastly different experiences and inspiring stories; people who pursued science at the expense of anything outside its realm, be it childhoods, friendships or relationships. Perhaps we might conclude that, actually, scientists are a cut above the rest, believing more than most in their ability to make a difference and improve society, life, and the world. But then I remember their fondness for wearing conference t-shirts and I despair.

They’re nothing out of the ordinary, there’s no such thing as a mad scientist, and none of them are superheroes. As The Flaming Lips put it, “they’re just humans.”

Nick Crumpton is a 3rd year PhD student in the Department of Zoology