SUNDAY, 22 JANUARY 2012

Thirty years since the first reported case of AIDS, effective treatment for the prevention of HIV transmission has yet to be found. The increasing prevalence of HIV worldwide has made such a discovery even more pertinent today. In 2009 alone, 34 million people were infected with the virus, and nearly 2 million people died.While many researchers in the field are attempting to confer immunity through vaccines, this new method involves immunization by gene transfer. It actually manipulates the genetic code of muscle cells to enable them to produce stable antibodies that target HIV for destruction.

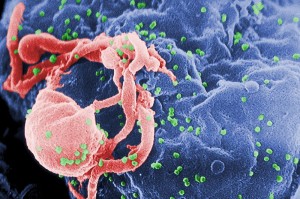

The researchers who developed this novel therapy at the California Institute of Technology and the University of California, Los Angeles, have termed it “vectored immunoprophylaxis.” It uses an adenovirus, delivered intramuscularly, to encode for neutralizing antibodies that recognize a protein expressed on the surface of the HIV virus. This protein, known gp120, plays a vital role in helping HIV infect the CD4 T cells of the immune system.

Mice given a single dose of the adenoviral therapy sustained higher levels of CD4 T cells than those not given treatment. Additionally, these mice sustained production of the gp120 antibody for a minimum of 52 weeks and at serum concentrations 100-fold greater than levels achieved with other vectors. The mice’s spleens also showed no staining for antigens expressed by HIV.

This work demonstrates that it is feasible to translate the existing repertoire of neutralizing antibodies into functional HIV therapy for animals. In humans, the antibody’s half-life is even longer, so its effects may be even longer lasting. Future clinical trials will prove how efficacious this novel therapy may be for humans.

Written by Leila Haghighat

doi:10.1038/nature10660