WEDNESDAY, 18 JANUARY 2012

The american philosopher and psychologist John Dewey once wrote, “Every great advance in science has issued from a new audacity of imagination”. Creativity within science and technology is not limited to scientists — we are used to seeing fantastic and seemingly impossible inventions in literature, films, art and theatre. Are these inventions confined to the realm of science fiction or, in hindsight, are they surprisingly accurate predictions?Consider something as simple as the automatic door. It was first invented by Lee Hewitt and Dee Horton in 1954 and is now commonplace in offices, shopping centres and even some public toilets. However, the idea was imagined first by H.G. Wells in 1899. In his novel When the Sleeper Wakes he writes, “...A long strip of this apparently solid wall rolled up with a snap…”. Admittedly, the leap from door to automatic door isn’t that impressive, and Wells gives no description about how this device actually works, but his forward thinking is still quite incredible considering he wrote this more than 50 years beforehand.

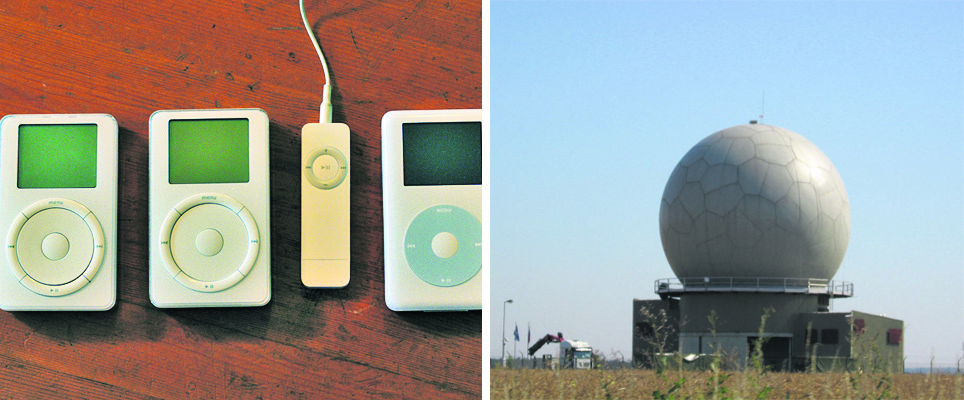

As a better example, let us take a description for a device to image objects using electromagnetic waves: “A pulsating polarized ether wave, if directed on a metal object can be reflected in the same manner as a light ray is reflected from a bright surface… waves would be sent over a large area. Sooner or later these waves would strike a space flyer…and these rays would be reflected back”. This accurate explanation of the concept behind RADAR was taken from Hugo Gernsbacks’ novel Ralph 124C 4+. Published in 1911, Gernsback illustrated the principle of the RADAR years before the scientist Nikola Tesla described the concept. While the prediction is surprisingly accurate, it still contains errors based on incorrect scientific understanding when it was written, in this case in its reference to ether, a substance thought at the time to permeate all space and allow the propagation of waves such as sound and light.

The late Steve Jobs was an individual hailed for his creativity and ingenuity in developing many new electronic devices for Apple. Nevertheless, even he would have to concede that he didn’t always get there first. What about the white earbud headphones that debuted with iPods? In the 1950s Ray Bradbury wrote in Fahrenheit 451, “And in her ears the little seashells, the thimble radios tamped tight, and an electronic ocean of sound … coming in.”

Even the invention of something as recent as the iPad with its 21st century design and sleek finish was foretold in literature. In 2001: A Space Odyssey, written 40 years before the first Apple announcement, Arthur C. Clarke writes, “When he tired of official reports and memoranda and minutes, he would plug in his foolscap-size newspad into the ship’s information circuit.... One by one he would conjure up the world’s major electronic papers”.

While all of these examples might lead you to believe that scientists should be reading science fiction novels to inform their latest research, we should remember that for every startling prediction that turns out to be close to reality, there are a dozen ideas that remain a distant possibility. Although, considering what has been thought of already, we may well have our personal robot companion and jetpack someday. One thing is clear: as scientists, it is important we never forget the power of imagination.

Matthew Dunstan is a 1st year PhD student in the Department of Chemistry