FRIDAY, 25 JANUARY 2013

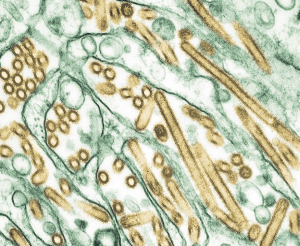

“Don’t panic” – these cautionary words, made famous by Douglas Adams in his book The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy, should perhaps be engraved above the door of the National Science Advisory Board for Biosecurity (NSABB). Their kneejerk reaction to censor the publication of two papers, each outlining how avian influenza, or bird-flu, might be engineered to spread more easily between humans, came close to causing a ‘panic pandemic’.Highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) H5N1 virus can infect humans and even causes death in some cases. However, this virus is currently unable to transmit between humans in the same way that normal flu can – through coughing or sneezing – and has only been transmitted to people who have had contact with infected birds. Several research groups have been investigating the spread of flu in ferrets (the best model of flu in humans) with the goal of understanding the likelihood of a bird-flu pandemic.

Ron Fouchier, principle investigator of one of these groups, won the battle to report his recent findings when his paper “Airborne transmission of influenza A/H5N1 virus between ferrets” was published in full in Science, overriding the NSABB recommendation that the manuscript be published in a redacted form. By withholding key details that would allow the paper to be replicated, the cornerstone of modern scientific research would have been compromised; all findings and methods are published in full in a peer-reviewed journal to encourage professional scrutiny, critique and replication, thereby ensuring scientific accuracy and progress.

The NSABB is a federal committee comprised of representatives of the scientific community who unanimously voted for censorship due to the potential to misuse the findings. The NSABB maintained that it was possible for terrorists to use this research to create a highly infectious influenza strain that could be used in a bioterrorist attack. The committee was particularly cautious over this case because HPAI virus is reported to kill over half of the people it infects, in contrast to 1 in 1000 for a typical infection. This is comparable lethality to the ‘Spanish’ flu outbreak of 1918, which killed more than 20 million. Estimates of lethality are, however, likely to be over-estimations as they only include patients who attended hospital with acute symptoms, thus discounting all those who have mild responses to the virus.

The Centres for Disease Control and Prevention have produced a list of agents that could be abused by bioterrorists, including infective viruses and bacteria, such as influenza, which spread through a population infecting many people long after the initial attack, and isolated toxic chemicals, for example Botulinum neurotoxin, which only affect those directly exposed.

Surprisingly, bioterrorism has been around for a long time. Hannibal, one of the most successful naval commanders of the 1st century BC, was known to fill pots with venomous snakes before he threw them onto the decks of rival boats during warfare. In the 14th century, Tatar forces hurled corpses infected with The Plague (Yersinia pestis) over the city walls of Kaffa during a siege. By contrast, there have been only four incidents of bioterrorism in the ‘modern’ era, two of which resulted in fatalities, both from the use of anthrax (Bacillus anthracis).

In 1979, at a military facility in the Ukraine, a technician forgot to exchange a crucial filter on a machine holding powdered anthrax. The machine was switched on and dispersed a cloud of the toxin over the city of Sverdlovsk, killing 100 people. Subsequently in 2001, letters laced with anthrax were sent through the mail to a number of media offices and US senators by a rogue employee of Fort Detrick, a US defence laboratory, causing five deaths. In both cases the release of anthrax was from an officially sanctioned facility that was permitted and equipped to safely contain and use the toxin. Without this, it would have been unlikely that the bacteria could be grown without infecting the person handling it. The two remaining non-lethal attacks were carried out by terrorist groups, the only reason we know this to be true is because they confessed afterwards.

In a ploy to prevent people voting in the 1984 Wasco County elections, followers of the Rajneeshee group deliberately caused food poisoning to 751 people by contaminating salad bars in 10 restaurants in Oregon with bacteria (Salmonella enterica). Although 45 people were hospitalised, none died and the authorities assumed it was accidental until a year later.

This case highlights a key flaw in bioterrorism – that attacks can be mistaken for natural events, negating the desired effects on the public psyche.

Nine years later the Japanese cult Aum Shinrikyo attempted an attack using airborne anthrax. The attack failed, because the cult had used the strain of the bacterium utilized for vaccinations, which cannot cause disease. This blunder demonstrates that a bioterrorist needs a strong scientific background to carry out an attack successfully.

That makes a total of 105 deaths known to be caused by biological agents since the turn of the 20th century. The comparisons between this figure and the lives lost from terror attacks, such as 9/11, need not be laboured to make a point. These examples illustrate the difficulties of manipulating biological agents; without secure handling facilities and specialist knowledge. Potential bioterrorists are likely to accidentally harm themselves without infecting others and certainly without making a political point or inciting terror.

Previous research into ‘Spanish’ influenza virusfurther emphasises the irrational nature of the NSABB’s response to bird-flu research. Several key papers on ‘Spanish’ flu have been published in full, although it ostensibly proves a similar bioterror threat, if judged by the NSABB’s standards.Censorship only attracts attention to the potential hazards and further incites public fears regarding the possibility for insidious use of scientific research. By blocking communication of scientific ideas we risk being unprepared for the natural progression of influenza towards a highly lethal and contagious form that is much more probable than a successful bioterrorist strike.

Paul Keim, director of the NSABB, controversially said, “I can’t think of another pathogenic organism that is as scary as this one”, in reference to HPAI. This is a typical response to the media hype that has surrounded new forms of flu virus in recent years, inciting public fears. Understanding how these viruses spread is crucial to preparing for a pandemic if it happens. For this approach to work, all the information needs to be available to scientists. This need is greater than the remote chance that the information will be used in destructive acts.

Were the NSABB’s concerns about “Airborne transmission of influenza A/H5N1 virus betweenferrets” justified? Three months after the call for censorship, the board reversed its decision, agreeing that revised versions of the papers should be published in full. Perhaps they allowed their initial fear to cloud their judgment when weighing the benefits of this research against the actual threat of bioterrorism in the modern age.

Sarah Smith is a 3rd year PhD student studying virology at the Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute