MONDAY, 3 MAY 2010

Faced with the prospect of making ourselves bikini (or speedos) ready for the upcoming summer, armed with delusions of self-belief and willpower, many of us will join a university sports club or start a new healthy eating plan. Maintaining a healthy weight is a case of eating less and exercising more. Simple, right?We are all aware that obesity in the western world is at epidemic proportions; the World Health Organisation predicts that by 2015, 700 million adults will be obese. Moreover, obesity has well-established associations with type-2 diabetes, reduced life expectancy and cardiovascular complications. Overcoming this condition is a major target for 21st century society. So, cut out the Big Macs, go for a run…how hard can it be? But keeping weight off can be a constant battle for some people, as anyone with Prader-Willi syndrome will tell you.

The syndrome is a relatively rare neuro-developmental disorder, caused by loss of gene expression, or the deletion of a region of genes on chromosome 15. The exact genes involved are still not known. Sufferers have learning disabilities and, most strikingly, severe obesity. From birth, babies with Prader-Willi develop more slowly and are extremely floppy (hypotonic). These are the key symptoms of the disorder in newborns. As infants, affected children show very little interest in food, and many have to be tube fed. In later childhood, this disinterest in dinner time evaporates and is replaced by over-eating, an obsession about food and the desire to eat almost all of the time.

People with Prader-Willi need around three times the calorie intake that healthy people need before they feel remotely full, and this feeling of satiety often disappears within minutes. Some sufferers will resort to eating raw meat, frozen foods, pet food, and in extreme cases, even items such as coal, when food is not available. Losing weight is made even more tricky by the fact that the syndrome is associated with a lack of muscle tone, and some sufferers also have problems with coordination, making exercising more difficult.

Prader-Willi syndrome is not solely a disorder of obesity, but has other striking characteristics that make the syndrome unique. Professor Tony Holland, the Health Foundation Chair in Learning Disabilities and a consultant psychiatrist for Cambridgeshire and Peterborough NHS Trust, is a leading researcher in this field. He explains: “Prader-Willi syndrome shows a very complex array of biological, psychological, social and clinical characteristics, and these often vary between individuals. For example, Prader-Willi is also associated with short stature, an unusually high pain threshold, and in rare cases, vomiting.”

Through his work, Tony Holland frequently comes face-to-face with the tremendous stigma associated with obesity that causes Prader-Willi sufferers to face unfair accusations of laziness and greed, rather than a recognition that they face a constant and life-long struggle to restrain from eating.

Treatments that have proved successful in other types of obesity, such as pharmacological agents and weight loss surgery, have either proven unsuccessful or have led to severe complications, even death. Currently, the only effective management strategy is life-long rationing of food, which severely limits the independence of sufferers.

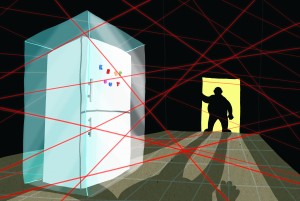

Parents living with children or adults who have Prader-Willi often resort to locking the fridge or putting alarms on food cupboards. The feeling of incessant hunger can lead to frequent tantrums when food is denied, increasing the strain within families. Additionally, even family members can find it hard at times to accept that this is not simply due to a lack of willpower. The constant requirement for watchfulness and restriction can be wearing.

For some, the only option is supervised living in specialised care homes, which may be better-equipped to deal with the symptoms and associated behaviour of Prader-Willi. For many people with Prader-Willi, the establishment of specialised care homes has been significant in helping them to help themselves in the constant battle against obesity. The heart-rending reality of this condition was illustrated in a 2007 documentary on Channel 4, Can’t Stop Eating, following the day to day lives of people with Prader-Willi living in Gretton Homes, a specialised residence for sufferers.

But Prader-Willi syndrome is not the only genetic disorder of obesity. Professor Stephen O’Rahilly and Dr Sadaf Farooqi at the Metabolic Research Laboratories at Addenbrooke’s Hospital have been involved in huge advances in understanding the genetic control of food intake, particularly in the discovery of obesity disorders caused by changes affecting a single gene. One such disorder is congenital leptin deficiency, which leads to over-eating and under-developed gonads similar to that seen in Prader-Willi. This disorder can be dramatically improved using leptin replacement therapy. However, so far none of the genes identified in other disorders of obesity are candidates for direct involvement in Prader-Willi. Nevertheless, it is thought that looking carefully at advances in other genetic models of obesity could shed light on the abnormal mechanisms in the syndrome.

Some mechanisms that have been identified are connected to food intake regulation, which is governed by a complicated interplay of gut and brain signaling, involving the hypothalamus and areas associated with emotion and motivation. Supporting this, brain imaging studies have shown abnormalities in various regions in the brain in Prader-Willi patients. Interestingly, these abnormalities are most pronounced after eating, supporting the view that the problem in Prader-Willi is not so much a voracious hunger, but more to do with failing mechanisms of satiety.

This year marks the 7th international conference of the Prader-Willi Syndrome Organisation in Taiwan, an event held every three years, and Tony Holland is optimistic: “We are learning more about Prader-Willi syndrome every day. We are looking for ways to help people with Prader-Willi and are undergoing pilot studies into treatments that could potentially help to overcome the over-eating. The picture is complex but I think it provides us with an amazing opportunity to understand the physiology behind obesity and food intake.”

Thankfully, with increased information about Prader-Willi syndrome, and access to genetic testing, parents are more aware of the disorder and can prepare themselves for its implications. Growth hormone therapy is becoming increasingly common in people with Prader-Willi to combat short stature, and has been successful in helping some people avoid the life-threatening obesity to some extent. However, the desire to be satisfied remains a chronic problem and one that still puzzles scientists and clinicians.

Kate McAllister is a research assistant in the Department of Psychiatry