MONDAY, 25 NOVEMBER 2013

Back in the 19th century a new terrifying disease was sweeping Europe. People would rapidly develop symptoms including vomiting, watery diarrhoea, muscle cramps and severe dehydration (indicated by sunken eyes, wrinkled skin, fast heartbeat and low blood pressure). Less than 24 hours after they first became ill, the person would be dead. Although cholera had been around for hundreds of years, this new strain, known as Asiatic cholera, was particularly frightening due to the severity of the symptoms and the speed with which an outbreak could spread and kill. It was also indiscriminate, killing not only the old, the young and the ill but also healthy adults. In 1831-1832 more than 32,000 people died.By the time of the first outbreak of Asiatic cholera, the industrial revolution had led to a mass exodus of people from the countryside to the towns and cities. Most people lived in squalid conditions and it was not uncommon for one room to be shared by five or more individuals. Many houses had cesspits in the basement and refuse was left rotting in the street, so it is not hard to imagine how incredibly unpleasant cities such as London would have been. For this reason, many doctors believed that diseases, including cholera, were caused by poisonous vapours, the so-called ‘miasmatic theory’. These vapours, or miasmas, were thought to be given off by sewage, refuse, graveyards and even people themselves and spread in the air before entering the body and causing illness. But could this really explain how cholera was transmitted from person to person, or how the disease would often disappear just as quickly as it had appeared?

In 1836, a trainee doctor called John Snow arrived in London to begin his training at the Hunterian School of Medicine in Soho. A shy man, he was vegetarian and a teetotaller, which led to him being thought of as rather peculiar by his peers. Nonetheless, he applied himself whole-heartedly to his studies and by 1840 had set up his own medical practice in Frith Street, Soho. Originally from York, Snow had spent time as an apprentice to a Newcastle surgeon and worked at the Killingworth coal mine, seeing at first hand the devastating impact of cholera during the 1831 outbreak.

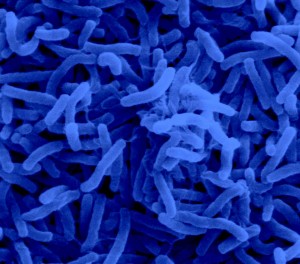

In 1848, cholera returned. Many Soho residents were affected and this prompted Snow to investigate what might be causing it and how it was spread. He postulated that if, as the miasmatists believed, cholera was transmitted in the air, the victims’ lungs would be clearly damaged. However when he performed autopsies on cholera victims, he found that instead the small intestines and bowel were inflamed and showed signs of disease. Snow also studied samples of water collected from households affected by cholera in the hope of identifying what might be causing the infection. Although he didn’t observe the tiny bacteria (Vibrio cholerae) which we now know cause cholera, he postulated that the consumption of “materies morbi”, or disease-causing particles, in the water was to blame for the disease. Snow published his findings and ideas challenging miasmatic theory in a pamphlet entitled ‘On the Mode of Communication of Cholera’ and waited for the response of the medical community.

Unfortunately, Snow’s pamphlet went largely unnoticed. Despite this, Snow remained convinced that cholera wasn’t spread in the air and a few years later another outbreak provided him with the opportunity to collect more evidence for his theory. On 31st August 1854 more than a dozen people in Soho developed the symptoms of cholera and just two weeks later over 500 people had died. Snow set about conducting door-to-door enquiries, drawing up a list of the dead and their addresses. He then marked each case of cholera on a map of Soho. This provided a striking indication that cases were clustered around the Broad Street water pump in Soho and the incidence of cholera decreased as the distance from the pump increased. In addition, Snow’s enquiries turned up a number of other interesting findings; a woman living in Hampstead who died from cholera had water collected daily from the Broad Street pump (as she preferred the taste of it) and had received one such delivery the day before she began to develop symptoms. In addition, the workers at the Lion brewery never touched the water from the Broad Street pump, instead preferring to drink beer, and none of them developed cholera. Although this evidence left Snow in no doubt that cholera was spread by contaminated water, he realised he still needed further proof.

Snow had noticed that cholera death rates were very high in South London during the 1848-1849 epidemic and at that time two water companies supplied the area with water taken from a polluted part of the Thames at Battersea Fields. However, in 1852 the Lambeth water company moved its waterworks further upstream to Thames Ditton, which was far less polluted. Meanwhile the Southwark and Vauxhall water company kept their Battersea Fields site. When Snow compared the death rates of customers of the two water companies during the 1854 epidemic, he found that 38 out of 44 households suffering cholera deaths had their water supplied by the Southwark and Vauxhall water company. Furthermore, Southwark and Vauxhall customers were almost nine times more likely to die of cholera than those of the Lambeth water company.

Snow published his work in a second edition of his cholera pamphlet, leading to the removal of the now infamous Broad Street pump. However, beyond the confines of Soho, it had very little impact. Ultimately, the fact that John Snow was just a doctor with a small medical practice and very little influence meant that his work on cholera was largely forgotten following his death in 1858. At the time of his death he was instead known for studying and optimising the administration of anaesthetics; he had even been called upon to give chloroform to Queen Victoria during the births of two of her children. It was not until the 1930s that John Snow’s work was rediscovered by a new generation of epidemiologists (people investigating disease outbreaks), who saw his systematic investigation into the spread of cholera as a clear indication of the importance of their subject. Although cholera outbreaks do still occur—one of the most recent being in Haiti following the earthquake in 2010—thanks to John Snow we now know how cholera is spread and how to limit the number of people affected by it.

Laura Pearce is a postdoctoral researcher at the Institute of Metabolic Science at Addenbrooke’s Hospital