SUNDAY, 17 JUNE 2012

From Ke$ha’s Your Love Is My Drug to Jake Gyllenhaal’s Box Office hit Love and Other Drugs, pop culture continuously compares love to drug addiction. The many examples inspire the question, is there a neurobiological explanation for why we draw comparisons between love and drug addiction?Both love and drug addiction are characterised as powerful drives causing intense yearning, either for one's romantic partner, an addictive substance or a particular behaviour. Although poets, musicians, novelists, anthropologists, and psychologists alike have grappled with the challenge of defining exactly what love is, it is a seemingly universal concept that incorporates cognitive, emotional, behavioral and erotic components. Addiction is similarly difficult to define, described also as an enduring cluster of cognitive, behavioral and physiological symptoms, which the Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders ‑used to diagnose mental illness-refers to as "dependence." In ways akin to addiction, romantic love is often said to grow exceedingly difficult to control. Falling in love is frequently associated with changing priorities and narrowing of behavioral repertoires, such that considerable amounts of time and resources are spent on one’s partner. The same type of narrowing of priorities could be said about people suffering from addiction.

Additionally, the devastation that occurs when a loved one is lost by either the intentional ending of a relationship or by death, in many cases looks like drug withdrawal. Although the exact symptoms of folklore’s "heartbreak" are, to my knowledge, not a topic of scientific investigation, it could be argued that heartbreak symptoms, such as difficulty concentrating, depression, irritability, anger, sleep disturbances and weight gain are also common to drug withdrawal. If the same neural processes underlie love and drug addiction, it may explain why they share a seemingly similar cluster of experiences.

Compared to the substantial research on the neurobiology of drug addiction, research on the particular neurobiological aspects of love is still in its infancy. Along with studying humans, pair bonding behavior in voles is arguably the most common model for studying love. One species, the Prairie vole, forms monogamous pairs, whereas a closely related species, the Meadow vole, is promiscuous and never stays with one particular mate. By comparing these two species of voles, researchers have the opportunity to study the neurobiology of pair bonding and attachment as a model of love.

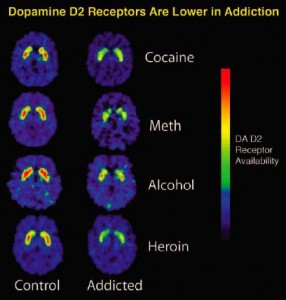

Neuroimaging studies in humans, and other experiments employing voles, reveal some neural correlates that are specific to love, particularly in response to hormones involved in reproductive behaviours, such as testosterone, oestrogen, and notably oxytocin, which is known to be critical for mother-infant bonding. However, dopamine is another chemical that appears to be a key player in the neurobiology of love, as well as a common factor between love and drug addiction. Dopamine is one of the main chemicals in the brain that is responsible for feeling good. There is substantial evidence that the brain’s dopamine-dependent reward circuitry underlies many aspects of addiction, and now there is a growing consensus that the same reward circuitry underlies social behaviors, including love. It seems it is the dopaminergic reward system that is common to the neurobiology of both love and drug addiction and may explain the surface similarities.

The dopaminergic reward system is a network of neural structures that produce or respond to dopamine. Dopamine has been implicated in the drug-related learning and neuroadaptation which are theorised to underlie addiction. The vast connectivity of the reward system may explain why addictive substances and love affect such a wide variety of behaviors, motivations and physiological processes. Because the release of dopamine is responsible for the rewarding properties of a wide-variety of stimuli and behaviors, it is not surprising that it plays a role in both love and addiction.

Although the literature comparing love and addiction is sparse, some researchers have considered the similarities, such as Thomas Insel at the US National Institute of Mental Health, and Helen Fisher of Rutgers University. Insel questions whether drugs take advantage of the neural circuits, such as the dopaminergic reward pathway, that likely evolved for behaviorally relevant rewards, including love. Insel's perspective is interesting in that, instead of asking "Is your love my drug," it asks "Is the drug a substitute for love?" suggesting that drugs replace the endogenous factors normally provided by love.

Fisher argues that love should be considered an addiction because of the associated euphoric highs, cravings, obsessions, personality changes and apparent loss of self-control. In support, Fisher emphasizes human brain scans taken using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), revealing several regions, many of which are part of the aforementioned dopaminergic reward system, that are activated by both romantic love and addictive drugs. Fisher also suggests that lovers exhibit relapse in similar ways to drug addicts, such that even long after the dissolution of a relationship, certain events may trigger a craving or impulse for a past lover.

The comparisons drawn between love and drug addiction are not to suggest that love should have a negative connotation. Thus, it is important also to acknowledge the major differences between love and drug addiction. Most obviously, unlike love, drug addiction is thought to be maladaptive and negatively impacts upon health. In most cases, love is associated with positive effects on health and well-being, with the exception of unreciprocated love. For example, marriage appears to benefit health whereas after a divorce people are more likely to suffer from health issues such as high blood pressure and weak immune systems.

The seemingly uncontrollable nature of romantic love, most notably the cravings for one’s romantic partner, suggests behavioral similarities between love and drug addiction. With the caveat that love is most often not maladaptive, both concepts reflect dependencies that engage the dopaminergic reward circuitry in the brain. The similar neurobiological signatures likely explain some of the comparable experiences in love and addiction. Because of the substantial evidence that love and addiction reflect similar biological processes, love does appear to be analogous in many ways to an addictive substance. Thus, pop culture appears justified in drawing comparisons between love and drug addiction and it is very possible that Ke$ha is right, and “your love is my drug.”

Brianne Kent is a 1st year PhD student in the Department of Experimental Psychology