MONDAY, 3 OCTOBER 2011

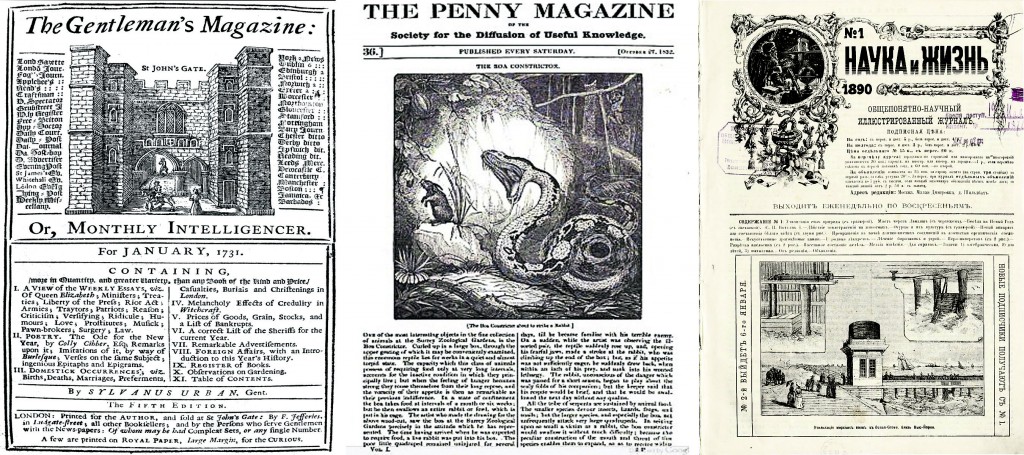

The streets of eighteenth century London bristled with endeavour. Home to many of Europe’s self-styled ‘enlightened’ thinkers, it was here that the world’s first ‘magazine’ hit the printing presses. The Gentleman’s Magazine, founded in 1731, offered the discerning public informative articles on a wide range of topics, including politics, history, economics and new scientific advances. In its first volume a report on the “conduct of the ministry” lies only a few pages away from a piece about the “credulity of witchcraft” and “observations in gardening”. Page nineteen sported a keen defence of “Mr Cheselden’s intended operation on the drum of the ear” and in subsequent issues medical features are as common as pieces about new technological advancements.Despite its varied content, the magazine’s intended readership was limited to a subsection of society: as its name suggests, the target audience was wealthy and male. This reflected the general philosophy of the Enlightenment in Europe which, despite encouraging civil liberty and self-improvement for the masses, was led predominantly by the educated and the economically powerful. Alongside dry academic journals, popular periodicals emerged, and among them, this newly termed ‘magazine’. Storehouses of novel and improving information, these new publications provided a way for science to enter the household of the ordinary professional, allowing individuals to rise to the challenge set by philosopher Immanuel Kant: “dare to know”.

‘Enlightening’ magazines were by no means the first attempts to disseminate scientific information. The Royal Society had been publishing its Philosophical Transactions since 1665 and even in ancient times the Greeks produced pamphlets relating to knowledge of the natural world. However, the eighteenth century marked the first time that science was presented as a source of self-improvement for the general public as well as a topic of general interest. As cheaper periodicals began to appear, this opportunity was made available to a much wider audience.

In 1826, the Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge was established in Britain. This explicitly aimed to educate the masses and began to publish The Penny Magazine in 1832. Like many of the philosophical and political works of the Victorian era the articles published within it were for the most part anonymous. This helped to protect authors with unorthodox views but also enabled the magazine to act as an authority and a purveyor of fact. Readers could expect to learn about exotic creatures from all over the British colonies as well as great advancements in the age of industrial revolution. Alongside the new breed of professional scientists, professional science writers also began to emerge: the number of popular science periodicals doubled from the 1850s to the 1860s.

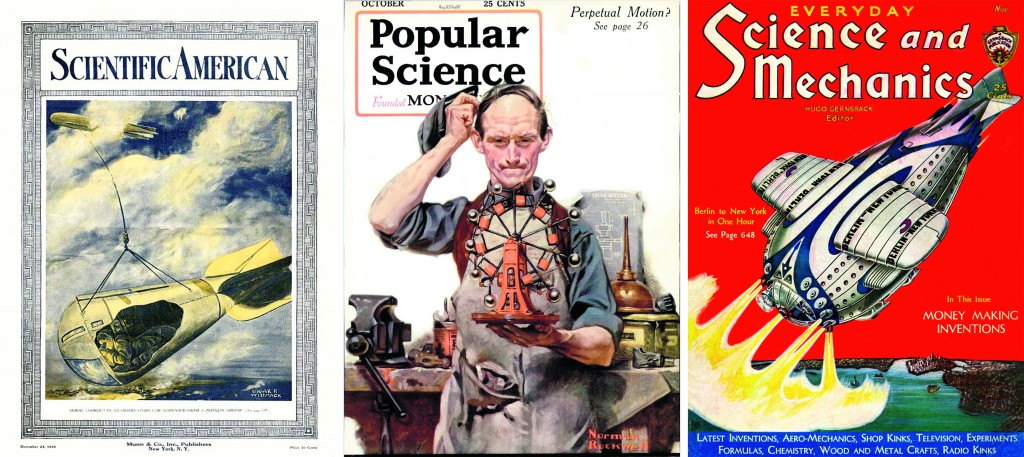

Across the pond, prolific inventor Rufus Porter founded Scientific American in 1845. The publication, which started out as a weekly four page newspaper, now sells monthly editions to hundreds of thousands of readers worldwide. In its early days Scientific American focused on the latest innovations, reporting on new patents and curious inventions. Its archives also contain evidence of early scientific debate. The edition of 11th October 1862, for example, features a caution against the use of oil for fuel; a view we might be tempted to call forward thinking. It reports advice to the American government to “stop further pumping and boring for oil” from “a gentleman who has spent some days in the region of the coal oil wells in Pennsylvania”. The warning was based on this gentleman’s own theory, which predicted dire consequences. He argued, “The oil is being drawn... from the bearings of the earth’s axis,” which “will cease to turn when the lubrication ceases.” Since this was around the time that large-scale oil drilling began to take off, we might now wish that this claim had been taken more seriously at the time, even if his reasoning was a little off. Nonetheless, we can see how, even 150 years ago, scientific magazines provided a forum for discussions about important issues; issues which continue to challenge governments, international relations and humanity as a whole.

Soon after, in 1872, a new magazine called Popular Science Monthly was put into print. Continuing the approach of the popular Enlightenment periodicals, it aimed to provide the educated layman with scientific knowledge and received contributions from a wealth of high profile scientists including Charles Darwin, Louis Pasteur and William James. Yet early issues would be judged dry by today’s standards and, with lengthy articles and few illustrations, it was more of an academic journal than a magazine. During the First World War, under the care of a new editor, it underwent a transformation and soon shifted towards more, shorter articles with colourful pictures, thereby dramatically increasing its circulation.

In the twentieth century the development of the scientific magazine continued to reveal much about the changing position of science within society, with each new issue providing a record of collective interests. Wartime pages of Scientific American and Popular Science are filled with expositions of the latest planes and weaponry; they seem to have been as much propaganda tools as informative guides. The tensions of the Cold War are also captured in the pages of New Scientist’s back issues, which date back to 1956, and in Russian magazines, such as Nauka i Zhizn (Science and Life).

Nowadays, magazines such as New Scientist and Popular Science have millions of subscribers worldwide and are storming ahead in the growing online and portable device industries. Yet these modern magazines are starkly different from their early predecessors. Rather than dry, authoritarian pieces they play host to scientific debate with clear, attributed articles and an emphasis on evidence. The divergence between academic journals and popular media outlets has enabled scientists to assess new findings in their chosen fields as well as engaging with work from other areas. With scientists working in ever more diversified disciplines on ever more collaborative projects, the need for general as well as specialist science publications is as important as ever.

Helen Gaffney is a 3rd year student in the Department of History and Philosophy of Science