MONDAY, 4 JANUARY 2010

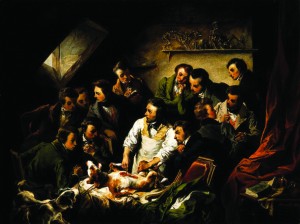

Society has gained immense benefit from research involving animals. According to the Royal Society, virtually every medical achievement in the past century has relied on the use of animals in some way. Today, animal experimentation is used for scientific and medical research only under stringent controls; this has not always been the case.The first documented use of animals in research can be traced back to Aristotle in ancient Greece. His observations of physiology led him to classify animals into the two groups that we now call vertebrates and invertebrates. In the 2nd century, the Roman physician Galen studied the function of the kidneys and spinal cord. Dissection of human corpses was illegal, so he relied on the vivisection (dissection of a living body) of pigs and monkeys. As scientific research became more commonplace, so did the use of animal experiments, which became mainstream during the 18th and 19th centuries.

In the late 19th century, immunisation was in its infancy. Louis Pasteur was studying diseases, including chicken cholera, when a batch of bacteria spoiled and failed to induce the disease in chickens that were infected with it. Further attempts to infect the same chickens failed because the weakened bacteria had given them immunity, whilst causing only mild symptoms. He tested this as an immunisation technique against anthrax in cattle, stimulating wider interest in tackling disease in this way.

Similarly, life-saving organ transplants could not have been developed without animal research. Dogs and pigs were vital in the development of the techniques, which started with French surgeon Alexis Carrel’s study of rejoining severed nerves. By the 1950s, transplants were routine, but the organs, such as kidneys, hearts and livers, were frequently rejected by the recipient’s body. Immunosuppressive drugs, which are now used after all transplant surgeries, were developed in the 1970s to prevent rejection. Once again, animal tests were vital in this. Kidney transplants alone now save about 2,000 patients a year in the UK.

From drugs such as insulin and antibiotics, to surgery and treatments for cancer and HIV, almost every conventional medical treatment that we rely on rests in part on the study of animals. In fact, it is a legal requirement to ensure that new medicines will benefit and not harm human recipients. The importance of appropriate tests is highlighted by the case of the drug thalidomide, which caused defects in limb development in the children of women who took it during pregnancy. Although thalidomide was tested on animals, effects on foetal development were not directly investigated. Rigorous tests must now be carried out before drugs can be sold.

It was once believed that animals felt no pain, so their suffering was not a consideration. However, we now understand not only that they do feel pain, but also that causing test subjects undue stress affects experimental results. With this knowledge, attitudes towards animal testing have changed considerably.

People began to advocate regulation in the early 1800s, leading to The Cruel Treatment of Cattle Act in Britain in 1822. Although not specific to animal testing, it acknowledged poor treatment and was a first step to regulation. Animal testing is directly addressed in both the 1911 Protection of Animals Act and the 1986 Animals (Scientific Procedures) Act.

Ethical questions in animal testing have always provoked strong debate and many organisations have arisen to protect animals and question their use for study. The philosophies and tactics of such groups vary, ranging from peaceful demonstrations to physical, sometimes violent action.

The National Anti-Vivisection Society, one of the first such groups, was at the forefront of British news between 1903 and 1910. The Society condemned the vivisection of a brown terrier during a physiology lecture at University College London as cruel and unlawful, and caused controversy by building a memorial statue of the dog. The statue was frequently vandalised and clashes known as the ‘Brown Dog Riots’ followed. Tired of the dispute, the council removed the statue and destroyed it. A new one was commissioned in 1985 and resides in Battersea Park.

Anti-vivisection organisations have also targeted individuals. Colin Blakemore, former chief executive of the Medical Research Council, was targeted by animal rights activists whilst working at Oxford University. They reacted violently to his research into child blindness during the 1980s. This involved sewing kittens’ eyelids shut from birth to study the development of their visual cortex, an approach which, according to Blakemore, directly helped to tackle the condition in humans. However, he and his family endured over a decade of abuse, including razor blade-filled letters, bombs sent to his home and physical assault.

Not all protests involve such violence. During the 1990s, a poster campaign showing cruelty in cosmetic testing on rabbits provoked public outrage and led to the ban of such testing in Britain in 1998. The European Union (EU) has since agreed to phase in a total ban of animal testing for cosmetics throughout the EU from 2009 onwards, and a near-total ban on the sale of such products. Such legislation has forced companies to find alternative testing methods, including the use of donated retinas and lab-grown skin cells to test for eye and skin irritation. It is these kinds of alternatives that opponents of animal research want to see used in all experiments.

In another example, Huntingdon Life Sciences, a contract animal testing company, was brought to the brink of collapse by the campaign group Stop Huntingdon Animal Cruelty (SHAC) through largely non-violent means. At the peak of the campaign in 2000, shareholders were named in newspapers and the company’s bank closed its account to distance itself from the controversy. The company moved its financial centre to America, where greater protection was given to shareholders’ anonymity, and has since recovered financially. This episode directly led to the government taking a firmer line against animal rights extremism. The police conducted a number of raids against SHAC and seven leading members were found guilty of blackmail.

Such protests have to be taken into consideration when planning for new testing facilities and research institutions. The planned Cambridge Primate Centre was abandoned in 2004 due to such concerns. The additional cost of supplying security against large scale protests and worries over public safety meant planning applications were rejected. However, in 2006, demonstrations against another new facility in Oxford led to the formation of Pro-Test, an organisation in support of animal experimentation. The group supported the construction by countering the arguments of anti-vivisectionists and attempting to raise public awareness of the benefits of animal research to mankind.

Under current legislation, scientists are required to search for realistic alternatives before they can be licensed for animal tests. They must consider the ‘three Rs’ first defined in 1959; refinement, reduction and replacement. Refinement of the procedures used so that suffering is minimised; reduction in the number of animals to the lowest required for meaningful results; and replacement of experiments on live animals by non-animal alternatives wherever possible.

When confronted with the ethical issues that animal testing presents, it can be easy to overlook the significance it has played in our lives. Modern medicine would not exist without it. Medical research in particular depends on understanding not only the processes of the living body, but also how they interact. Currently, only animal tests are able to capture this complexity. However, in the past 20 years, the number of animals used for testing has been halved, and with the search for alternatives such as lab-grown cells and computer models now a high priority, the number of animal experiments needed will continue to decrease.

Lindsey Nield is a PhD student in the Department of Physics