THURSDAY, 5 NOVEMBER 2020

Their work was published in Nature Communications and followed from a previous discovery, which showed that T cells dampened the immune system by releasing immunosuppressive steroids to reduce activity to normal levels post-infection.

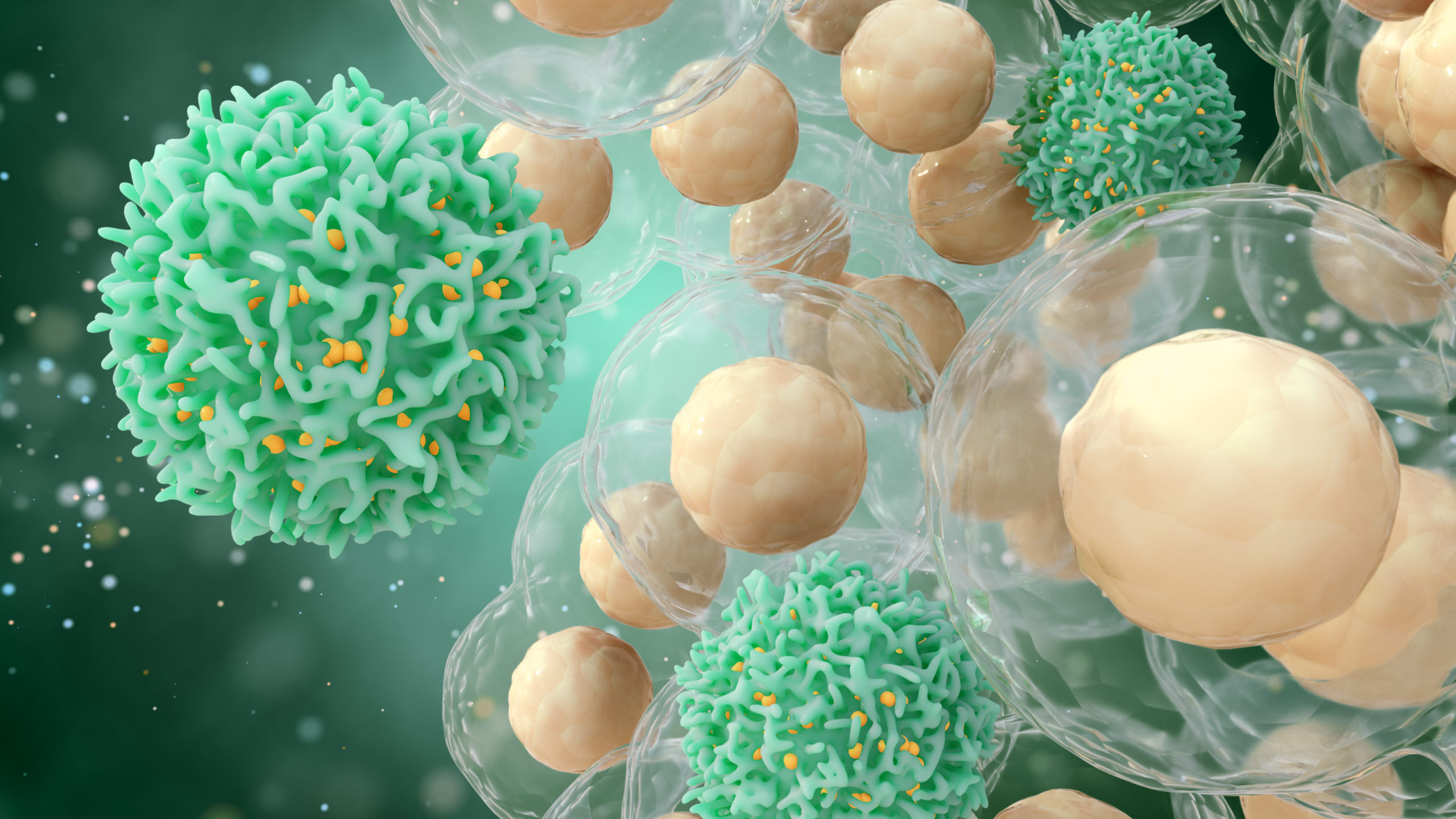

Their subsequent research in mice reported that T cells from melanoma and breast tumours behaved in a similar way. Using single-cell RNA sequencing, the team discovered that the tumours tricked T cells into producing immunosuppressive steroids, while those T cells from healthy specimens did not.

To test whether stopping steroid production could reduce tumour growth, researchers examined mice without a key steroid-synthesis gene, Cyp11a1. As expected, the tumours in these animals were dramatically smaller than those in ordinary mice. According to Dr Sarah Teichmann of the WSI, ‘Preliminary data from human tissues suggests the same tumour defence may happen in people’. If true, future drugs could target this immunosuppressive pathway as one way to treat cancer.

This article was written by Jacob Whitehead, an MPhil student in Criticism and Culture at Trinity Hall College.