MONDAY, 4 JANUARY 2010

As a scientist, darwinist and atheist, I may be expected to join with Dawkins and his disciples to worship science and spurn religion. But religion is an integral part of humans as a species and cannot simply be removed. For me, those that preach science while belittling faith neglect the positive influence of religion and are in danger of losing the respect of the public.Religion is deeply rooted in human history as both a consequence and an element of our evolution. An overgrown brain provided our hunter-gatherer ancestors with cognitive abilities that allowed our enormous success as a species: ingenuity and imagination were central to survival strategies. Yet the side effect of conscious thought allowed our ancestors to contemplate the world and their own existence within it. The resulting need for explanations – the same need that we possess today – most likely formed the basis for religious belief.

It is easy to imagine how supernatural beliefs emerged in a hunter-gatherer civilisation. Many factors drastically affecting survival were beyond human control: weather, disease, availability of food. Appeals to envisaged rulers of nature may have helped our ancestors feel that they had some influence over their own survival.

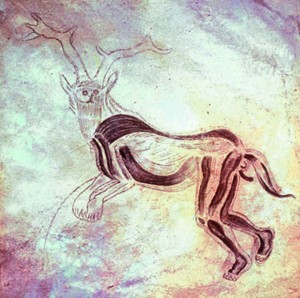

Evidence of these practises has been seen at archaeological sites. Cave paintings depict the performance of rituals to communicate with the spiritual world and ensure successful hunting, most notably a 15,000 year-old picture in the Trois-Frères Cave in France. Head dresses found at other sites also suggest that such rituals took place. The first written accounts of theistic entities, over 4,000 years old, refer to gods of the weather, animals and planets, further evidence that such beliefs originated earlier with hunter-gatherers and became ingrained over hundreds of generations.

For such prominent behaviour to have persisted from so early and for so long, religion must have had a strong benefit for the survival of the species; had it not, natural selection would have ensured that it was not so universal or eradicated it entirely. Ironically, those who worship Darwin and his theory should be more aware of this than anyone. To write off religion as unimportant is surely to dismiss a crucial element of human evolution.

Our predisposition to religious notions means they will not simply vanish. In a 2006 poll conducted in the US by Time magazine, 81 per cent of those asked said that recent scientific advances had not changed their religious views at all. What’s more, 64 per cent said they would not discard a particular religious belief even if science directly disproved it.

So if discrediting religion scientifically will not change religious beliefs, the currently fashionable mixture of logical reasoning and ridicule will not do any better. Whilst the logic may bolster the case against religion, the ridicule will surely undermine the argument. After all, what is ridicule but a demonstration of arrogance, a display that implies the stupidity of others for having an alternative view? The implication of this attitude is that science holds all the answers and that it is where we should look to for all human improvement. But for most, science is of little use when it comes to the emotional, real-world experience of human life.

By all means tell people about science, present them with the logic. But meandering into the territory of openly judging people because of what they believe, and telling people how they should and should not think, gives rise to the accusation that scientists are preaching a religion of their own. Is this an impression that the scientific community wants to convey? Will it encourage public minds to be open when contentious scientific questions are presented to society? Perhaps when reaching out to the public, scientists should concentrate less on pointing out the flaws in religion and more on conveying the richness of life that science can uncover.

Ian Fyfe is a PhD student in the Department of Pharmacology